In Conversation with Devan Shimoyama: On Unapologetically Celebrating Black Male Queer Bodies

Courtesy of the artist.

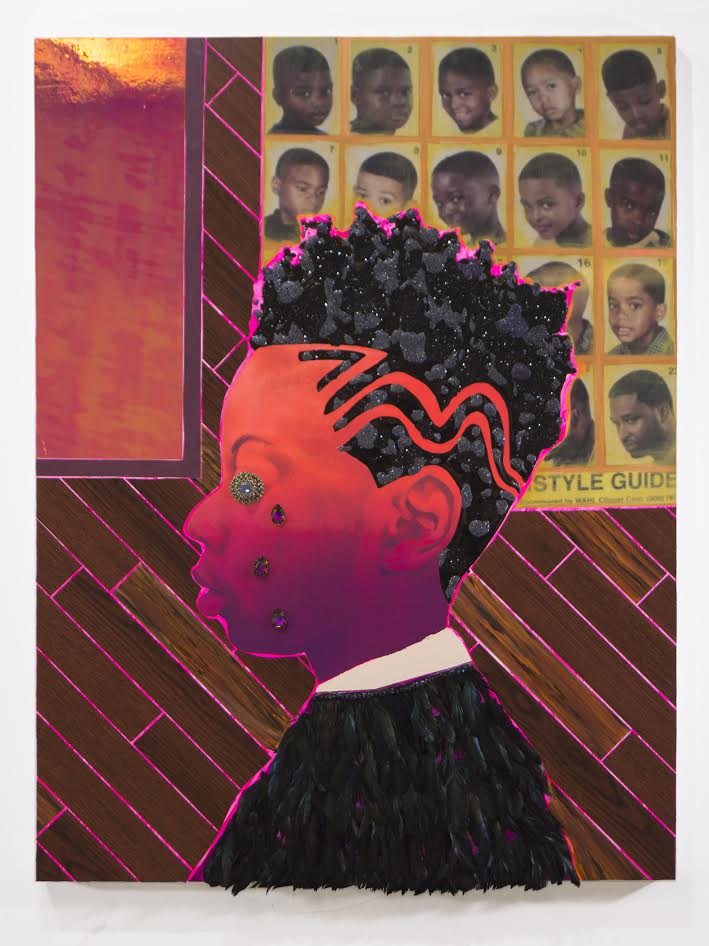

Contemporary artist Devan Shimoyama (he/him) unapologetically celebrates black male queer bodies in such a fantastical and wondrous fashion. I find him to be a younger millennial counterpart to Mickalene Thomas, his mixed-media canvases are bejeweled and bedecked with glitter, rhinestones, and shiny textiles, and focused on highlighting the beauty of black (queer) figures. In his recent solo show, Sweet, at De Buck Gallery, around twenty works, each work hypnotic and captivating, addressed making space for gay black men within black barbershops. The Philly native and Yale MFA grad has had a spectacular year, having shown at the Independent Art Fair, most recently at Pulse Art Fair in Miami, and is also included in Fictions, a superstar POC group show at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

Gallery Gurls: Your new show, Sweet, explores expanding the barbershop, a hyper-masculine and heteronormative space for black cis men, as a safe space to include black queer men. Can you tell me more and did you look to your personal history as well to talk about this?

Devan Shimoyama: This body of work on view at De Buck Gallery in my show Sweet conceptually came out of conversing with other black gay men about our experiences in black barbershops. Throughout the duration of the show and especially during the opening, I was able to meet so many new people who immediately relate to those same experiences expressed in the work, and felt like the work functioned as a call to a community of individuals who could really understand each other. In black barbershop settings, men form a fraternal bond and engage in heteronormative discourse that at times does not allow room for queer voices. I've seen fathers reprimand their children for crying, playing with other boys, displaying effeminate behavior, etc. in the barbershop. I've heard from friends who are more femme that they've been snubbed or turned away or treated poorly and I've myself even had to listen to other men in the barbershop using homophobic and misogynistic language. While all of this is problematic, I intentionally made an effort to not vilify the black barbershop or those who seek community there, hence why the barber's identity in these portraits are never shown. I instead, sought to construct my own fantasy, an over-the-top queer/drag/femme barbershop in which black males can truly convene and decompress and cry and express themselves as they truly are. The only barber shown in these works is the self-portrait entitled CTRL where I'm depicted cutting my own hair in my bathroom mirror. In recent years, I've really mastered cutting my own hair, and often cut the hair of friends.

"I instead, sought to construct my own fantasy, an over-the-top queer/drag/femme barbershop in which black males can truly convene and decompress and cry and express themselves as they truly are."

Crowned, 2017, Devan Shimoyama. Courtesy of De Buck Gallery.

I noticed many of the subjects in these new works are young black men and boys, do you think there are messages in the work directed towards young black men grappling with gender and their sexuality?

I’d love to have some interactions to hear what young boys feel when seeing the work, but I have yet to see that. I think the work is maybe more directly relating to young black men who have shared this experience in their youth. For me, a lot of the materials are also signifiers of my own youth and triggers nostalgia; the wood-paneled walls are from my grandparents basement where I’d often get my haircut in the comfort of my own home by my uncle, the silk flowers being something that was used for decoration in the living room (which was forbidden for children to play in and was primarily for show), etc. Even the posters on the walls (the Obama Hope poster, the old school haircut chart) all are these remnants that still can be found in barbershops locally, but have aged over time on the walls. I think the work points to issues and seeks to find a fictional space of security and comfort for all forms of black masculinity. I’d love to do more community-based projects with barbershops and youth to just initiate a conversation, but I do not assume that the work is accessible to young black boys in the gallery space. Especially not to the communities in which those with shared identities to those individuals depicted.

CTRL, 2017, Devan Shimoyama. Courtesy of De Buck Gallery.

With the black hoodie sculptures, the unnecessary loss of young black males comes to mind (Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, etc) What do these pieces signify?

The hoodie is a reminder to all black men of the true dangers of how black masculinity can be reduced to this emblematic image and that we need to unite and be kind to one another regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity. So, certainly inspired by the deaths of Trayvon and others that followed in the string of highly publicized young black male deaths via police brutality in recent years. It’s an urgent call to my community to unite.

"The hoodie is a reminder to all black men of the true dangers of how black masculinity can be reduced to this emblematic image and that we need to unite and be kind to one another regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity."

Installation of Sweet, Devan Shimoyama. Courtesy of De Buck Gallery.

Installation of Sweet, Devan Shimoyama. Courtesy of De Buck Gallery.

You’re also currently included in the group exhibit, Fictions, at the Studio Museum in Harlem, the fifth iteration of this seminal 'F' exhibition series. Can you talk about the inclusion of your work Shape Up and a Trim in the show?

That work is a part of the same series of works in Sweet. It was made simultaneously with those works. I was asked to participate and recently participated in a panel discussion at the Studio Museum with Amy Sherald and the two curators of the exhibition, Connie Choi and Hallie Ringle. The discussion covered things such as how we approach fiction and fact in our practice, the significance of portraiture, black bodies in art, etc. It was wonderful to be able to unpack some of that in conversation with another figurative painter!

What’s next for 2018? What can you share?

I’ll be showing in a few upcoming group exhibitions, but can’t disclose that information just yet. Otherwise, what I can discuss is that I’ll be having my first solo museum exhibition at the Warhol Museum opening in October 2018! So be on the lookout for that. There will be a large survey of work I’ve made over the last 5 or so years, as well as quite a few new works!

Shroud II, 2017, Devan Shimoyama. Courtesy of De Buck Gallery.

Off the Charts, 2017, Devan Shimoyama. Courtesy of De Buck Gallery.

Unititled, 2017, Devan Shimoyama. Courtesy of De Buck Gallery.

Follow Devan Shimoyama @devanshimoyama