In Conversation with Ayana Evans: Her Black Womanhood as Performance Art

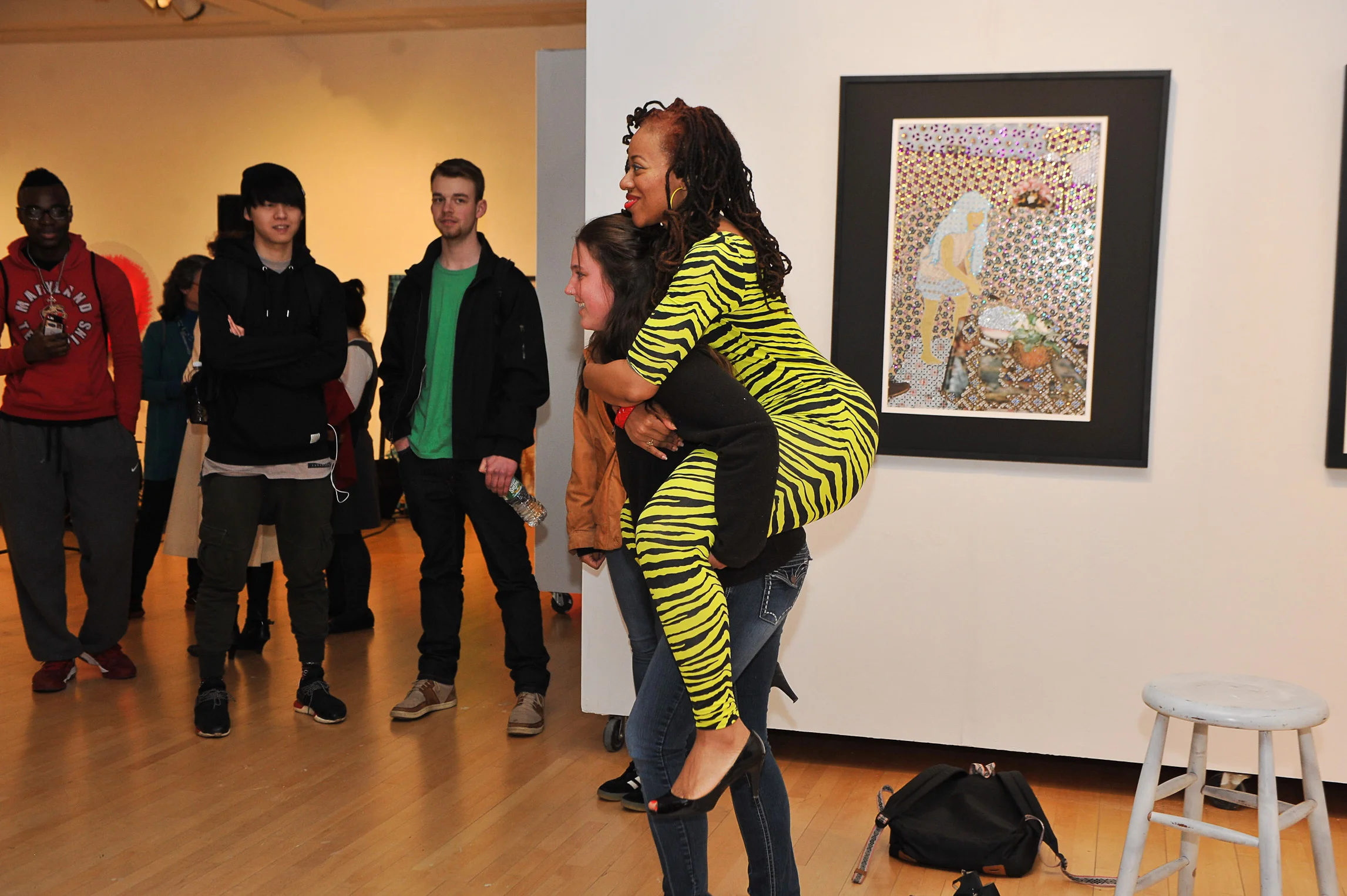

During Evans' residency at El Museo del Barrio. Courtesy of the artist.

I catch up with Ayana Evans (she/her), the magnetic and intoxicating New York-based performance artist fresh off Art Basel Miami Beach, who recently performed at two art fairs: Satellite Art Show and Prizm. Evans, a native Chicagoan and Brown MFA alumna, creates mesmerizing performance pieces pulled from an autobiographical place, and executed with physical intensity, while firmly exploring her feminist cis identity. The significance of Evans' performances is the simplicity of her messaging: finding a partner, achieving financial stability, and reaching personal and professional prosperity. These fundamental and pure goals are what makes her work undeniably relatable. I speak to the artist for a deeper dialogue about the black female figure and turning romantic woes into a coup for her art.

Gallery Gurls: You recently completed a residency with El Museo del Barrio. How instrumental was this in your artistic development? and what goals do you think you achieved?

Ayana Evans: I think this residency's value for my career is actually immeasurable. It was the first time in eight years that I had a studio space. The weight of that did not hit me until I was standing in an empty space with high ceiling and wanted to cry. When I applied I did not think I would get it and my main motivation was that I wanted to perform at a museum. Ironically, the residency was delayed for a year and a half and as a result when it began I was at a different point in my artistic practice. I had already performed in a couple of museum settings (El Museo and The Queens Museum both the year before) and I had begun organizing shows with other artists, which did a lot for not feeling like I HAD to be accepted into programs. As a result, my original plan for the residency was expanded to include a lot more artist collaborations, weekly themes, and group shows as well as solos performances within the residency. The weekly themes were: Werk/Work (physically strenuous performances while wearing heels and full makeup), Beauty Week, #Squadgoals Week 1 & 2, Dance Week, and Legends Week, which was canceled due to the police killing an unarmed man in my parents' backyard and the death of my cousin from cancer. The week really became Black Lives Matter Week. It was a crazy summer.

I spent hours talking to museum patrons, sometimes about love and looking for a husband, a lot of times about race and answering questions like "Why was I at El Museo if I was a Black American?" Repeatedly I explained what performance art was historically and/or what exactly I did within the art form. Leaving the safety and familiarity of the Brooklyn performance scene put me in front of a crowd that didn't know my past series. And I had to explain it and make everything engaging when it was new to the viewer. Simultaneously, the open invitation for performers to collaborate with me made me and show their own individual work within my space made me feel less ego-centered. This definitely strengthened the audience connection in my performances.

It was exhausting. I worked seven hours a day, five days a week for a summer arts program and then went to the museum and performed every evening. I performed while tired for the entire last month, but in a weird way the whole thing was a great exercise in stamina for me (which is great because all my work centers around stamina). I pushed my social media presence, I applied for grants to pay for documentation of the work, I created flyers to advertise myself and other performers, completed two photography-based collaborative series, and I called in a lot of favors. Most importantly, I hope I made it easier for future performance artists to be programmed into that museum.

"I wasn't the first performer at El Museo, but I proved group programming of emerging performance artists can be a draw for audiences there, without triggering administrative backlash, which I think is often the fear that stands between performance artists and institutional backing."

I am still seeing the benefits from that residency both in my career credibility and in how it has shaped my work. The independent curator who created the program was Nicolas Dumit Esteves and the museum's curatorial team, Rocio Aranda-Alvarado and Sofia Resser Del Rio, who were very supportive. I am fairly sure I will look back at last summer 20 years from now and see that a lot ideas and practices that began for me at El Museo del Barrio still emerging in my work.

During Evans' residency at El Museo del Barrio. Courtesy of the artist.

In Operation Catsuit, you attend several art world functions in a body-conscious zebra print catsuit to record people’s reactions, but on a deeper level do you think there was a fixation/fetishization/curiosity of a Black body in white-dominated spaces? What was your intent with this series?

My intent the first time I did this piece was to show a contrast that I saw when attending a fashion gatherings vs. art openings. At the time, I had left art for 6 years. I had been a painter and I ran out of ideas and didn't like painting anymore, so I quit. When I started Operation Catsuit I was at a point when I wanted to return to art and I needed to go to shows to get a grip on the art scene again, so I was going to both fashion and art parties. I found a marked difference in how a sexy woman at an art party was judged as unintelligent versus how that same woman was applauded at a fashion event. I thought this was interesting and I was a bit disturbed that once again I was in a space as a Black woman where I didn't feel I could wear whatever I wanted because of how it would be perceived, but this time it was happening in art. (how ironic)

I will admit that I did pick neon on purpose from the start because ,while I did not think race would be a big focus, I was also aware that I was frequently at events where I was either the only Black woman or one of a few in a room of 50. What if instead of trying to blend in I said "F*** it" and decided to completely stick out. This was on my mind from the beginning.

After doing to project for the first time at MoMA and reviewing the footage only to find that many white women who walked past me as though I didn't exist took photos of my butt behind my back, I quickly saw that what I thought was a one time "experiment" about fashion was a study in race and the Black female body. I began repeating the project in different neighborhoods. The only rule I stuck to was that I only performed this piece at art shows that really had an interest in seeing me with or without the catsuit. I added "audience" interviews after the first video to dig deeper into why my body was being fetishized so boldly.

From the I Just Came Here To Find a Husband photo series. Courtesy of the artist.

I Just Came Here to Find a Husband, stems from your frustration of not finding a romantic partner, but I love how you turned a setback into a triumph for your artistic practice. Can you expand on the meaning of this series?

This project is definitely the result of my frustration and desperation in my dating life! I wanted, and still want, a life partner, so badly that it hurts... and I'm getting older so the idea of not finding someone to have a family with is real. I reached a point where new ideas for art performances were not even coming readily because I was solely focused on my love life. So I decided to go to events that I would normally go to hoping to find someone, like the Spike Lee Block party or the Black Ivy Spring Gala, and tied a laminated sign on my back that stated "I Just Came Here To Find A Husband." In fitting with my usual performance practice of physical and mental endurance each time I wore it I walked for 2-4 hours wearing the sign (sometimes in the hot sun) all while answering personal questions, listening to romantic advice, posing for photos upon request, and explaining my performance practice. When I wear the sign women often high-five me and say, "Me too girl!" or "Glad someone said it!" This is part of why I keep wearing the sign.

Eventually, I made the 50 limited edition t-shirts because people asked for them. The same people who high-fived me when I performed the piece publicly wanted more from the project. I screenprinted the shirts myself and created signed labels that tell the customers what number they have from the edition (Ex. 14 of 50). I see the making of this performance art (object) as a way of giving fans of the project a collector's item, it is also inviting viewers to become an active part of this performance.

Being that getting married is a life goal that I previously tried to conceal, because I didn't think I could be a "cool art girl" and desperate for marriage at the same time, this project exemplifies what happens if you let everyone know what you are trying to hide. The underlying theme that I want people to take away from this project is to ask for what you want. It's not about me finding a husband. It's about me letting go of hiding that I'm trying to find a husband. You can come to find a Wife/Husband/Calling/Yourself. And sexual orientation alone can be your statement. I love that people send me pictures of themselves in the shirts or sipping from the mugs. They are truly embodying the project - showing the world what they want.

"The underlying theme that I want people to take away from this project is to ask for what you want. It's not about me finding a husband. It's about me letting go of hiding that I'm trying to find a husband."

Don't get me wrong. Conceptual ideas aside, wearing the sign makes me feel better. Now I don't have to hide that I'm looking for a husband (not a boyfriend - a husband) or bother with not mentioning it on a date because it might scare someone away. My art has emboldened me in that area. Ironically it made the desperation leave. People always ask if the project "worked," meaning did I find a man. No boyfriend yet, but I am talking to a guy I really like who knows exactly what I want and loves my art practices. It's early in the relationship. Fingers crossed that it works out. But if it doesn't I won't be crushed.

Evans as a curator during the 'Your Decolonizing Toolkit' performance with Esther Neff, IV Castellanos, and Maria Hupfield in “Feet on the Ground", New York. Courtesy of the artist.

For 'Your Decolonizing Toolkit’, you switched roles as a performer to curate instead (along with your fellow Cultbytes editor Anna Mikaela Ekstrand), and you touched on themes of black womanhood, artistic freedom, body politics, etc Can you tell me about your curatorial mission?

We really wanted to talk about race and gender and sexuality and limits. Anna Mikaela and I chose artists who pushed the limits of what is discussed concerning the perception of what is "acceptable" and who care about forcing their audiences to look at the world in a different way, whether that is because they are asking audience members to segregate piles of black and white rice while discussing their thoughts on race publically as Dominique Duroseau did or morphing soft shape objects with a dancer's body in a apartment doorway as Shani Ha and Amélie Gaulier did. The title was a riff on the title of work presented by Maria Hupfield, Esther Neff, and IV Castellanos, "Feet on the Ground" in which an actual toolkit is used to create the group performance presented. Other artists presented in the show were David Antionio Cruz, Kanene Ayo Holder. They also added the perfect confrontational spice for our event, sometimes making the audience squirm, but still hold court in a way that captivated us all.

Anna Mikaela and I were particularly focused on curating a show that did not divide artist by race, sexual orientation, or gender. There are often shows that present the same type of performance art or only black performance art or only feminist-centered performance art, etc To convey a theme that tackled a colonized mind and systemic bigotry we had to create a show that tackles that perspective in the compilation of artists. This was important to us.

We also felt it was important that we try to pay each artist. Anna Mikaela Ekstrand is particularly passionate about this. We paid out of pocket to give small fees to the each artist involved in the show. In this sense we are extending the idea of fighting bigotry to the economic realm. How can you support the ideas of mental and political freedom without supporting the idea of economic independence? You can't. Our society is not structured to afford power without money. Yet, many curators and institutions often leave performance artists out of the budget for events, both big and small.

"We also felt it was important that we try to pay each artist. How can you support the ideas of mental and political freedom without supporting the idea of economic independence? You can't. Our society is not structured to afford power without money."

From the performance Gurl I'll Drink Your Bathwater. Courtesy of the artist.

From the performance I Carry You & You Carry Me. Courtesy of the artist.

From the performance Stopping Traffic. Courtesy of the artist.

Fashion plays a big role in your performances, you’ve worn glamorous evening gowns accentuating your body and femininity in works such as Stay With Me, Gurl I’ll Drink Your Bathwater, Stopping Traffic, etc What's key about your appearance during these performances?

I think on many levels the emphasis on my appearance is a throwback to my past work as a painter and as a fashion designer. Those are visual realms. I often think of how I will look against the environment that I perform in. I prefer vibrant clothing and specific textures to obtain a desired vibrancy to my look, frame by frame. I love fashion and I enjoy serving a strong look. This is fun for me so I indulge in it. I hope to indulge in it even more in the future.

There is also the idea that I have always been taught as a woman that my looks matter just as much as what I think and how hard I work matters. This old way of treating gender roles is being played out in my work. I feel that presenting myself as dressed up - meaning wearing a gown, heels, and full makeup - I am making a statement on doing these performances as a woman. It is harder to do jumping jacks for 3 hours in heels as I have done in Stay with Me. It is even harder to do perform this act with a face of full make up and a gown. Makeup sweats into my eyes and the fabric around my legs makes them harder to lift, but I look good as preserver for the performance. I think that makes the work a visual metaphor for how I am struggling to "make it" in the art world. The goal is to stay sexy while I do it. And as I see it, "staying sexy while you do it" is what many marginalized people are forced to do to succeed in many fields across this country.

"Most of the outfits highlight my shape which is that of a curvaceous Black woman. Dressing up this body for presentation is also a political act. I don't want to be presented as basic. This is hard work and therefore special."

Courtesy of the artist.

So what’s next for you in 2017?

In the upcoming year I hope to push educational work. I have a project where I tutor students for the SAT and ACT while wearing my catsuit. The idea being that I am teach as my full self while also helping to even the playing field of education. (I usual hide the fact that I am a performance artist from my students) I'm hoping to get more financial support for this project in 2017.

During a performance at El Museo del Barrio. Courtesy of the artist.

Follow Ayana Evans on Instagram: @ayana.m.evans